December 9, 2020 — By the time Tombstone premiered on December 24, 1993, the 90’s western revival was in full swing. In truth, the genre had never truly gone away; its enormous popularity at the start of the 1930s all but guaranteed an enduring legacy.

Its tropes and conventions bleeding into other genres. To such an extent that it became inextricable from the many other Hollywood pulp genres. Enjoying cyclical revivals that would see it resurface every 20 years or so.

This was almost the exact case with the 1990s Dances With Wolves. The Kevin Costner vehicle that grossed $424.2 million from a $22 million budget. Which sent studios scrambling to re-explore the Wild West. While the Western never truly went away, the chasm between the enormous budgets of Hollywood productions and more independent fare highlighted a very real investment on Hollywood’s part to reintroduce the genre.

Whether it was Back To The Future Part III or An American Tale: Fievel Goes West, the Western setting was making a comeback in a big way. Perhaps explaining why two films went into production exploring the legacy of legendary lawman Wyatt Earp.

The first of these being Tombstone. Written by Kevin Jarre (of Rambo: First Blood Part II fame), and starring Kurt Russell, Val Kilmer, Sam Elliott, and Bill Paxton. The question of its director, however, is a complicated matter. Initially, Jarre himself was due to make his directorial debut with this movie. But after falling behind early on was fired by producer Andrew Vajna. Replaced instead by George P. Cosmatos (also of First Blood Part II fame, as well as Cobra). Except according to post-production reports — and hearsay from the actors themselves — the film was ultimately directed by star Kurt Russell, with Cosmatos only ghost directing. Stories of production strife tend to be a dime a dozen in Hollywood, but if Tombstone suffered for its change of creative personnel, it doesn’t show in the final product.

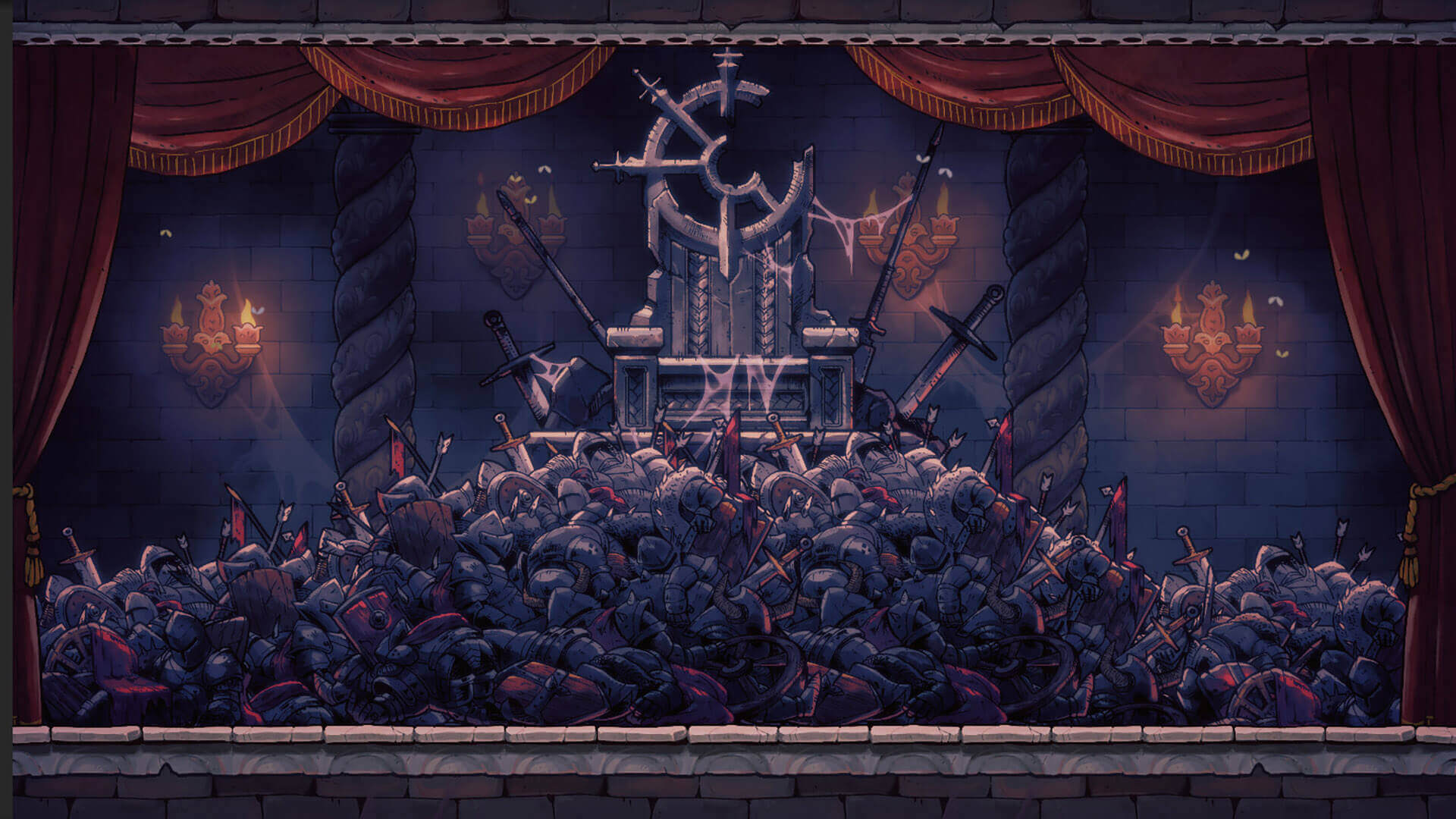

The movie opens with early shots from The Great Train Robbery (one of the first films in the genre), before introducing primary antagonists the Cowboys (identified by their red sashes). Massacring an entire wedding party, right down to the bride and priest who are dragged away screaming. Thus, marking both their lawlessness and most crucially godlessness. This sets up the film’s core theme of retribution, being delivered unto those who are not god-fearing. Which is an early allusion to the four-horsemen, setting up the roles of the main protagonists perfectly. Mirrored for effect later on when they begin their walk of vengeance. Cleaning the titular town of its blight in one of the film’s most iconic shots.

In truth, Tombstone owes more to 1988’s Young Guns, than to the likes of Wolves or Unforgiven. Building itself around an ensemble cast and placing a strong focus on the individual characters and their personality quirks. While each actor truly holds their own, ultimately, it is the pairing of Earp (Russell) and Doc Holliday (Kilmer) that produces the best results. Earp is portrayed as a world-weary stoic (later vengeful law-bringer with an Old Testament sense of justice), and Holliday, a silver-tongued intellectual with a death-wish. Kilmer here plays on the most maverick, wild tendencies of Holliday to really bring the role home. All the while keeping his vulnerability and suffering on the surface, betraying just how bad Holliday’s tuberculosis diagnosis was.

While bandits are a common foe within Westerns, the early identification of the Cowboys as ‘one of America’s first organized crime groups’ also neatly ties this film in with another major genre-revival of the 90s; the gangster film. Like how The Untouchables drew heavily on the ideas of the Wild West to create a thematic through-line. Tombstone resembles more modern crime fare. In its protagonist’s reluctance to return to a life of violence, and ultimate ride of vengeance against a wicked aggressor.